The Battle sites

You can visit the historical and archaeological Route of the Battle of Trasimeno in the beautiful area around Tuoro. Established in the 1980s using the approach outlined by Prof. Giancarlo Susini’s research into the scene of the epic battle between the Romans and Carthaginians. There are currently 9 parking areas in which various issues related to the Battle and the history of the places are covered. Stations No. 1 and No. 6 are particularly interesting. The first provides a wide panoramic view of the valley battle site with a view of the chokepoint of Malpasso, where the columns of legionnaires met their death. The second one, at the top of Sanguineto valley, overlooks the theatre of the battle according to Prof. Susini’s reconstruction. Work is ongoing to complete and enrich this open-air museum able to offer to Italian and foreign visitors with clear and complete information.

Before the battle After the victory at Trebbia, Hannibal continued south, convincing the consuls and the Roman Senate that his purpose was to march on Rome. In Val di Chiana he skirted around Flaminius’ waiting army, forcing Flaminius to follow his path of plunder. Thanks to precise information reported by his scouts, Hannibal decided to draw the Romans to the northern shores of Trasimeno Lake, an area well-suited to an ambush. He went through the narrow road called Malpasso, out of sight the enemy army, and placed his camp on the hill where Tuoro stands today.

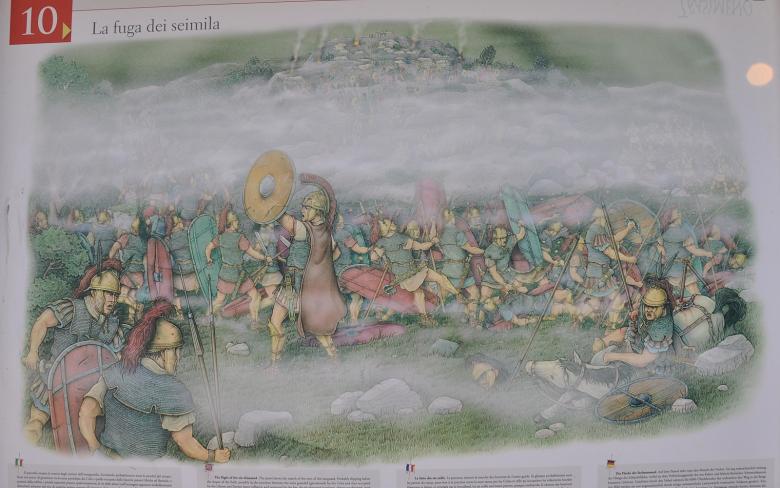

Roman Army The Roman army of 25,000 men, marched in columns through and continued into the plain at the foot of the Tuoro hills. Caius Flaminius decided to enter this valley without any reconnaissance, probably convinced that Hannibal's troops were more than a day away.

Carthaginian Army Hannibal’s army had an extremely heterogeneous composition. From the beginning he had African warriors (Numidians, Libyans, Maghrebis, etc.) and Iberian (Balearics, Guasques, Asturian Framboliers, etc.). During his victorious march, these were joined by Celts and the rebellious peoples of northern Italy, especially the Ligurians and Insubrians. By the time it approached Trasimeno, the Carthaginian army was reduced to about 40,000 men, because of the epidemic that broke out after crossing through swampy areas, and had lost all its elephants.

Archaeological references Many archaeological finds came to light in the area, especially during the nineteenth century, and many of them date back to the Republican or the first empire period: weapons, horse harnesses, buckles, coins, etc. Of particular note are the Etruscan-Roman statue The Orator of Trasimeno (late 2nd or early 1st century BC) and the bronze statue called the "Graziani putto", a copy of which can be seen at Tuoro’s City Hall (the original is in the Vatican Museums).

The Consul Caius Flaminius Historians judge the consul Gaius Flaminius as more politically than militarily able. The most severe critics describe him as impulsive and reckless. In any case, it should be remembered that in the general confusion of the battle he managed to remain calm, trying to reorganize his men, until he was struck by the Insubre Ducarius’s spear. His body was never recovered.

The battle At dawn on 24 June 217 BC, under a thick blanket of fog, most of the Roman army was already deployed in the plain. Hannibal had placed the light cavalry and the Celts at the entrance of the valley, to block any retreat, the Libyans and Iberians around his camp, the Balearic Islands and the Astati to close the pass on the slopes of the hill of Tuoro, which, according to Prof. Susini, was in close contact with the shore of the lake. (Following Nissen, the trap closed further east, between the slopes of Montigeto hill and the lake). When most of the legions had entered the valley, Hannibal gave the order of simultaneous attack: the battle lasted three hours and cost the lives of 15,000 Roman soldiers, some of whom had sought refuge in the waters of the lake.

The ustrini The truncated conical sections dug into the limestone and found in the Tuoro area might, according to some scholars, be burial systems, called "ustrina", built by Hannibal to incinerate the battlefield dead to avoid epidemics. Other authors believe that these are ancient kilns for the manufacture of lime.

The Orator statue This bronze statue represents an Etruscan prince, dressed in the typical toga praetexta of Magistrates and Senators, making an address. The statue, which was found in an area just south of Sanguineto, was transported to Pila di Perugia where, later, was sent to the Grand Duke Cosimo of Tuscany. Today it is found in the Archaeological Museum of Florence.

Roman column The Roman column was donated by the mayor of Rome to Tuoro (Trasimeno) on the occasion of the Conference of Hannibal studies in 1961 during which Prof. Susini presented his theory. It was installed in the fall of 1965 on the site believed to be the edge of the lake in 217 BC, in what is called Via del Porto. Recent investigations have shown that the old port “Casa del Piano", where the road led, was used from the late Middle Ages when the lake reached very high average levels that were maintained until the end of the 1800s.

The ancient shoreline According to studies by Prof. Susini, in 217 BC Trasimeno covered more terrain than it does today, so the ancient shore cut into the valley, making it smaller than what we see today. Recent studies place the coastline even further back than it is now. We can assume a vast battlefield, given the enormous armies involved.

Characters

Hannibal Fine strategist, daring warrior and maybe a bit of a sorcerer. This is the Hannibal handed down by historians: the man of a thousand tricks, able to win even in numerical inferiority thanks to his diabolical tricks. He proved his undoubted strategic abilities when he decided to reach Italy by land, thinking he could easily stir up the populations subject to Rome. He set out in the spring of 218 BC with an army of 50,000 men, 9,000 horses and 37 elephants. On his long journey he crossed the Pyrenees and the Alps where, due to the intense cold, he lost most of his elephants. He defeated the Romans by the Ticino and Trebbia rivers and reinforced his army with the help of the Gallic tribes. He crossed the Apennines and the swampy lands of the Serchio and the Arno, where many of his men were decimated by an epidemic and he himself had a serious eye problem. In 217 BC, he reached the hilly areas north of Lake Trasimeno and decided to quickly defeat the Roman army in order to increase his prestige and incite the cities of Etruria to rebellion. In that year, the Roman legions were led by the consuls Gaius Flaminius Nepos and Gnaeus Servilius Geminus.

Gaius Flaminius Nepos A member of the popular party and a courageous innovator in politics, Consul Gaius Flaminius had several detractors who pointed out his lack of military expertise. According to the most severe critics, Flaminius was reckless because he did not perform reconnaissance and so was trapped by Hannibal. This judgment must be partly correct. In fact, Flaminius was waiting to be jonied by the troops of the other consul Servilius, en route from from Rimini, so he chased the Carthaginian army for a long time, keeping his distance, without any hurry to engage in the clash. Outnumbered and in a clearly unfavourable position, his army was defeated by a military tactic that, for the Roman culture of the time, was unfair and in serious breach of the supreme value of fides (trust).

The Permanent Documentation Centre of the Battle of Trasimeno and Hannibal The Centre opened to the public in January 1996, in the Il Sodo park in town. The City of Tuoro tries to serve both the scientific and general audiences, with a collection of the entire bibliography on the subject, exhibits and models to reconstruct the main theories, and popular material on videotape and CD ROM. At the Centre visitors can view a permanent display on the Hannibal epic, with the entire Second Punic War told through images. The Centre hosts occasional meetings, conferences, debates, presentations of publications and magazines on the subject: today it is the point of reference for scholars and enthusiasts. The two main theories on the Battle of Trasimeno, which refer to the studies of Nissen and Susini, are compared in the Documentation Centre of Tuoro, in two large models that capture the moment of the Carthaginian attack at dawn on 24 June 217 BC. The relative environmental reconstructions, troops and equipment were made with hundreds of lead models. The two versions differ essentially in geographical-historical assumptions of the shoreline of Lake Trasimeno.